Studying fiqh presents a challenge to the modern Muslim mind. Due to the pressures of the modern world where Islam is the most controversial religion, we have come to define and understand certain Islamic topics, especially pertaining to Islamic law, in ways that are palatable to the secular mindset.

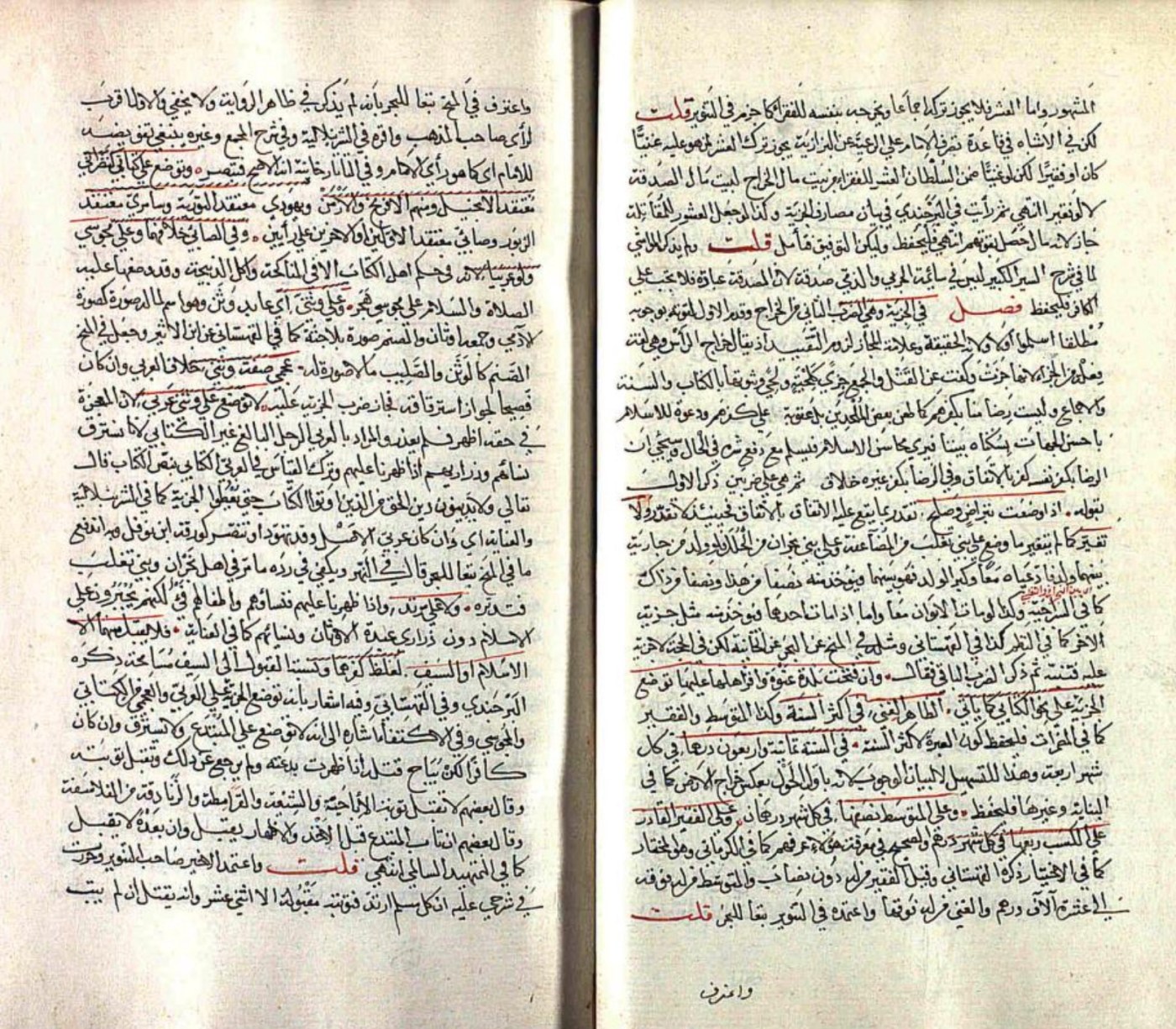

But, the well known fiqh manuals of our tradition present a window into a different world, a different time, when Muslims did not have to be apologetic about the shari’ah.

One such example is the relation between da’wah and jihad.

What comes to mind when we talk about da’wah these days?

Lectures? Videos? Leaflets? Debates? Street da’wah stalls?

As important as they are – and we definitely should continue these rewardable activities – Imam Haskafi tells us what is the best form of da’wah in his Al-Durr Al-Muntaqa. In the chapter on jizyah, he describes jizyah thus:

دعوة للإسلام من احسن الجهات بسكناه بيننا فيرى محاسن الاسلام فيسلم

The jizyah enables a political arrangement between Muslims and non-Muslims to live together under the rule of Islam, where the lives and wealth of non-Muslims are protected similar to the Muslims’. There is a statement of ʿAli (may Allah be pleased with him) found in some fiqh texts which states:

“They only offered the jizya so that their blood would be like our blood, and their wealth like our wealth.”

In a society where the justice of Islam is a living and breathing reality, that is where non-Muslims are truly able to witness the excellence of Islam and therefore more likely to accept it. That is why Imam Haskafi says that the jizyah is da’wah to Islam in the best of ways.

On a related note, it is worth quoting Wael Hallaq in relation to the justice that the shari’ah achieved in past Islamic societies, especially for the “social underdogs”:

Furthermore, the consumers of law and of the court’s services were themselves the loci of the moral universe. That those who initiated litigation in the court were the social underdogs is now certainly beyond debate. They were women versus men, non-Muslims versus Muslims, and commoners versus the economic and political elite. That they won the great majority of cases and that they found in the court a defender of their rights is equally a forgone conclusion. They appeared before the qadi without ceremony and presented their cases without professional mediation. They spoke informally, even disorderly, and employed the discursive and rhetorical techniques that, according to capacity, each could muster. That they could do so was testimony to a remarkable feature of Muslim justice, namely, that no gulf existed between the court as a legal institution and the consumers of the law, however economically impoverished or educationally disadvantaged the latter were.

Yet, it was not entirely the virtue of the court and qadi alone that rendered this gap non-existent, for credit must equally be given to these very consumers. Unlike modern society, which has become estranged from the legal profession in multiple ways, traditional Muslim society was as much embedded in a shar‘i system of legal values as the court was embedded in the moral universe of society. It was a salient feature of that society that it lived legal ethics and legal morality, for these constituted the religious foundations and codes of social praxis. To say that law in pre-modern Muslim societies was a living and lived tradition, is merely to state the obvious.

Therefore, a proper study of the Islamic sciences is necessary to help us refine or reevaluate our understanding of certain topics.

If you found this post beneficial, please share and subscribe below.

Leave a comment